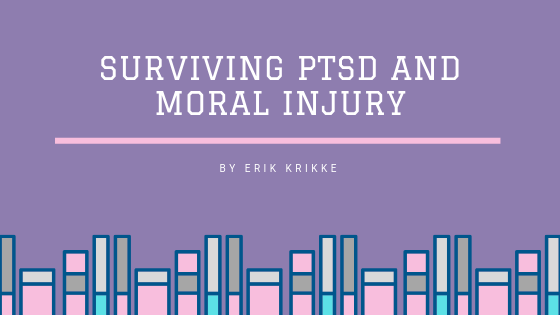

Surviving PTSD and Moral Injury by Erik Krikke

- Darya

- 05/02/2020

- Book Reviews

- 0 Comments

When I started reading this book, I didn’t really know what to expect. I was interested in the topic because our world is full of so much war and so many people are involved with the efforts. Recently, I’ve read a few books set in World War II, a time from which we are quite disconnected though the stories are still so fresh for some people. So when I picked up Erik Krikke’s memoir and saw the title “Surviving PTSD and moral injury” I didn’t know what I was getting myself into.

When I started reading this book, I didn’t really know what to expect. I was interested in the topic because our world is full of so much war and so many people are involved with the efforts. Recently, I’ve read a few books set in World War II, a time from which we are quite disconnected though the stories are still so fresh for some people. So when I picked up Erik Krikke’s memoir and saw the title “Surviving PTSD and moral injury” I didn’t know what I was getting myself into.

The image in my head of people who experience post-traumatic stress disorder has always been that of soldiers on the front line, because that is how it has always been framed to me. I have seen stories in the news and seen films about how difficult it is for front-line soldiers to reintegrate back into their old lives, and how that can lead to serious mental health issues and even lead to suicide.

Krikke’s memoir weaves through his experiences as a nurse in the operating rooms of a third world war hospital. The hospital in Kandahar where he worked was barely equipped with proper measures to ensure the degree of sanitation we expect in Western society operating rooms, and this opened my eyes to a world of war that many of us even forget exists.

We often see and focus on images the front lines or the devastation from bombings and shootings which affect innocent civilians in (sometimes remote) villages and cities. We then hear stories from those who survive these vicious attacks, with the trauma and sometimes even missing limbs. What we don’t see or hear about is what happens when the injured are taken to the place where there are teams of people equipped and ready to make sure they survive. We don’t hear about the medical teams who are among the first people to hear about attacks, those injured, and ultimately casualties who sometimes don’t even make it to the hospitals prepared to treat them.

What Krikke’s offers readers in the first half is an actual retelling of the experiences of someone who has been there. Krikke shares days in surgery that most of us would never expect to ever hear about, sometimes with lengthy and graphic detail for which I was admittedly not prepared for. Through his recollections, from his early days to the thick of his deployment, we are offered a glimpse into the mind of a person at war: not only the tangible war they are physically part of, but the war that is raging inside their own mind.

In the second half of the book, Krikke brings to light the pieces of his puzzle that lead to a PTSD diagnosis and his treatment. What was really important for me was to see that the compassionate and therapeutic resources that he was offered seemed to be available and useful because he sought them out.

This story is so important. Krikke was lucky to have been able to recognize that something wasn’t right with the help of his family, friends, and therapists. I hope that his story will open the conversation up for more people who come home from war-torn countries and experience similar things.

I received this book in exchange for an honest review in collaboration with Amsterdam Publishers.

Recent Comments